Most of The Betrothed Sister is set in medieval Russia where King Harold II’s daughter Gita (Thea in the novel) is married off by her father’s cousin, King Sweyn of Denmark, to a prince of the Rus ruling family, The Riurikid Dynasty, founded in the tenth century. What sort of land did Thea discover, circa 1070?

I always think of medieval Russia as a land of fairy tales, snow, castles, and sleighs. In fact over the years I have been so entranced by Russian fairy tales, that I constructed Thea, the heroine of The Betrothed Sister, as a teller of stories. Appropriately at the maiden’s party just before her wedding to Vladimir Monomarkh, I introduce a competition for the telling of fairy tales since, with this story, I aimed for a ‘fairy-tale’ atmosphere. These events happened so long ago that finding out what happened to Thea was difficult. However, with imagination and a thorough investigation of the times, I constructed a possible history for her.

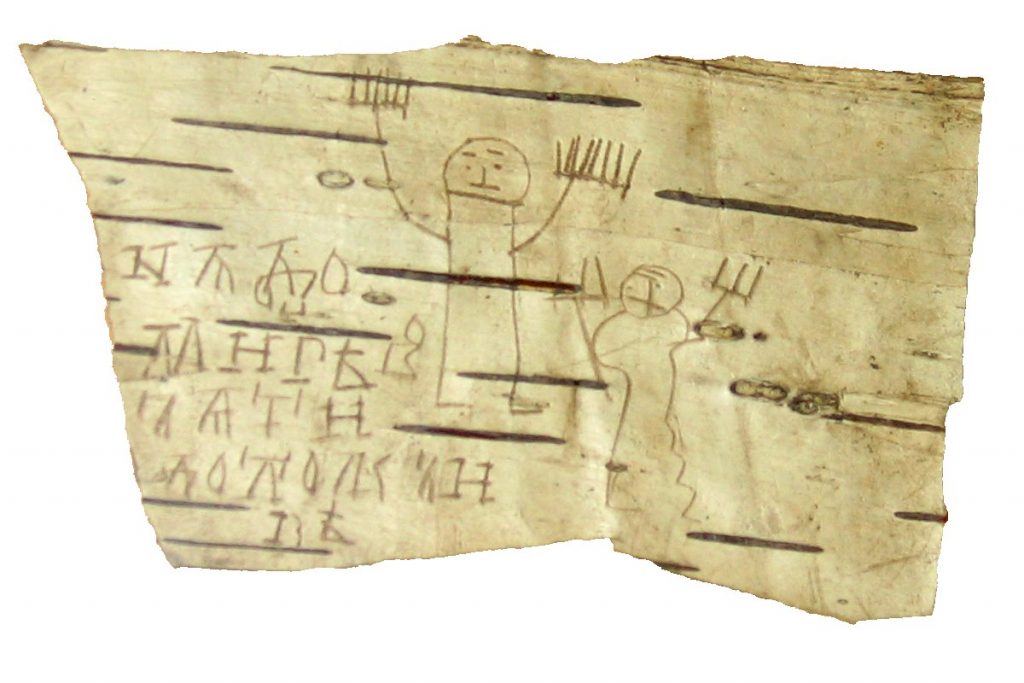

Medieval Rus was very different to Anglo-Saxon England, another extremely cultured society. This said, many exiles from the Anglo-Saxon world wound up in Kiev and Novgorod after the Norman Conquest. If Moscow existed at all, it was a simple village, totally insignificant. Kiev, the centre of the Rus Kingdom, was cosmopolitan and wealthy from trade along the River Dnieper from Byzantium. Novgorod, too, was equally wealthy and the discovery of birch wood tablets with shopping lists and love letters in Novgorod dating from this period, suggests a high level of literacy that is often found in established rich societies.

Thea sailed to a land where the Church had already become a second institution. As the ruling Riurikid Dynasty gave shape to the emerging Rus State, rulers looked towards Byzantium for a range of cultural influences associated with Christianity. A perfect example is, therefore, the development of the Russian Orthodox creed and a literature very influenced by Byzantine styles.

Writing and literacy existed within Rus lands during the tenth century. East Slavonic was used for practical, administrative and personal written application-type correspondence. With a Greek Orthodox influence, Church Slavonic drew on Slavic words and grammar and used them in Byzantine style, becoming the liturgical and formal literary language of the Kievan Rus. From the middle of eleventh century literacy and texts became more widespread. Clerics used Greek forms as models for their own compositions. Chronicles, recording the first written history of the Rus, were written in Church Slavonic. This gave the tribes that made up the Rus state a common cultural background. It also gave the Riurikid Dynasty an ideological foundation for exclusive rule over the Kievan Rus. Much of this literature is admired today. The Lay of Igor’s Campaign is an epic poem, written in old Slavonic, describing Prince Igor’s campaign against the Kumans in the twelfth century. It is unanimously acclaimed as the highest achievement in Russian literature of this Kievan era. Consequently, not to be kept in ignorance in her new land, Thea learned to read and write the literary language of her adopted country.

According to the Russian Primary Chronicle, in part written down in Kiev during the years encompassed by my story, years of fratricide dominated the eleventh century, often linked with Rus battles fought against the Kumans, the collective name for Steppe tribes dwelling on Rus borders. Warring princely Rus brothers would seek support from these organised, sophisticated and militaristic border tribes. Thea’s first decade in Rus lands was haunted by such rivalry between members of her husband’s family. It was all about succession to the important throne in Kiev. The family member who was crowned Grand Prince of Kiev ruled the kingdom of the Rus.

The principal of succession to the Kiev throne was that the senior member of the Riurikid princes of their generation would inherit the throne. Thus, it could pass to an uncle rather than to the eldest son of the eldest son. Brothers and nephews soon disputed this order of seniority established by Prince Vladimir’s great grandfather, another Vladimir. For instance, was seniority defined as chronological age or by the status of a wife? The Rus princes were monogamous, but despite warfare, it seemed that many of the Rus princes became widowers early in life and remarried, sometimes to Kuman princesses, never mind dynastic marriages into great European families. Thea married into such a situation. In 1068 the senior prince, Iziaslav, her betrothed Vladimir’s uncle was challenged by his cousin, Vseslav. This had a warlike outcome that lasted for a number of years.

For the early part of Thea’s marriage to Prince Vladimir, the son of a younger brother, there was a period of intense dispute over succession to the Kievan throne. Eventually, in 1078, Vladimir’s father gained the throne but became embroiled in battles with his nephews who felt they should inherit the throne from their father, Vladimir’s second uncle.

Thea sadly died before her husband inherited the Kiev throne from his father in 1113. Thea’s husband had become a pivotal figure in dynastic politics, greatly admired as a leader because he led a series of successful campaigns against the Steppe tribes, securing Rus southern borders. Thea’s sons followed their father as Grand Prince, one by one, and became in their turn rulers of the Rus. Thea is, in fact, the great grandmother many times removed of the Romanovs, the Russian royal family that ruled Russia in the first years of the twentieth century. It could be said too that, although, the Godwin dynasty did not hold on to England in 1066, King Harold’s elder daughter, Gytha/Gita/ Thea, gave them a long regal legacy.

The Betrothed Sister is published by Accent Press for all e devices, and as a paperback. It is available from all good bookshops.