In the December drawing of the Julian Work Calendar the nimble little figures that labour month by month are flailing, winnowing and taking away the produce of their harvest in baskets of fine woven wattle. The medieval Calendar is dedicated to work and prayer and its message is that you must labour as unquestioningly as you worship God. November was the time to cull animals that could not be fed during the winter, to preserve meat by salting it and the time to stack firewood. December was the time for threshing. And, of course, a time for celebration as it was, for all, the mid-winter Feast.

January shows pictures of the ploughman handling massive oxen just as if they were enormous machines. This energy helped produce the food that fed the medieval English man throughout the year. Their often hard life is depicted in an old Anglo-Saxon poem entitled The Fortunes of Man. The poem is a meditation on fate in which the author examined the different destinies that a child of this period might encounter as he grows into an adult. Although life was filled with hazards it could offer joy as well. In the poem, there is a wish list of sport, easy money and feasting and drinking. Just as the year turns the question hangs in the air, which way will an individuals life turn. Will it be to tragedy or to happiness. Wyrd or fate was a significant concept for the eleventh century Englishman or woman.

The Anglo-Saxon year was punctuated with feast days attributed to Saints. The most significant of these was the Christmas Feast. This feast was also an important communal act which reinforced social bonds and provided the occasion for the discussion of and dissemination of important information. Moreover in addition to a wide range of home-produced foods and drinks at the mid-winter feast, a noble family might have access to spices, herbs, wine, oils, fruits and nuts from abroad. Trade routes stretched from the Baltic to the Indian Ocean. Imports included coriander seeds, pepper and oil. Bede is recorded as having bequeathed lavender, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, coriander, cardamon, galingale, ginger, liquorice, sugar and pepper to his fellow monks on his death. So a Christmas or New Year’s gift may have included exotic spices and Christmas fare may have contained surprising exotic flavours. By the end of the period, the court, and other large households, appear to have secured suppliers of pepper. 10 lbs of pepper was paid at Christmas by subjects of the early medieval King Ethelred as part of a toll. By the eleventh century, pepperers were organised and established. Pepper was widely used to season omelets, in wort drinks, in honeyed apple dishes whereas we might use cloves.

Winter clothing is described in an old English poem called The Seafarer. The seafarer’s feet were so pinched by cold that he felt shackled by chains of ice. In Aelfric’s Colloquay the ploughman is very aware of the difference between his outdoor life and the comfort experienced by his lord. His boy’s voice was hoarse from the cold and shouting as he urged on the plough oxen. They needed clothing to keep out the rain and the snow and so the main material for wet-weather wear was leather. These garments included boots, ankle leathers, shoes and leather trousers. The leather maker in the Colloquy proclaims that ‘no-one is willing to go through winter without my craft.’ However the majority of Anglo-Saxon garments were made of wool, black, brown and white wool, spun, woven and dyed.

The King travelled around his estates with great worldly displays of daily rejoicing and feasting. Several hundred people would travel long distances to the king’s winter feast. And closer to the estates that spread throughout the countryside, workers entitlements varied, but a perquisite might be feasts such as Christmas, Easter as well as harvest, ploughing and haymaking feasts. The mid-winter Christmas feast was a special occasion enjoyed by all, labourers and nobles alike and it is recorded that the major festivals of the church were to be celebrated on the pain of excommunication. The Rule of Chrodegang stated that two or three drinks could be taken in the room with the fire but this rule also cautioned: ‘however great the gladness, see that drunkenness does not prevail.’ Yet, Christmas then as now was a special celebration. The Penitential of Theodore excused penance for the priest who drank too much on a saint’s celebration feast, or at Christmas! And after all there is Lent to come before winter is out and a long cold lean season ahead. I have written about The King’s Christmas Feast of 1065 here http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.co.uk/2012/11/christmas-1065.html#comment-form

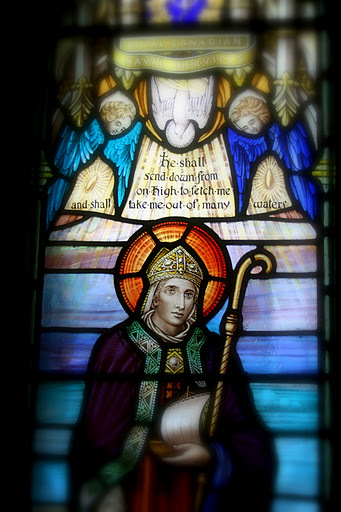

St Nicholas came later but he is always associated throughout Europe with Christmas. I love the richness of the stained-glass window painting above and could not resist including it here.

In the Liverpool museum there is a walrus tusk from the eleventh century that has been carved with two cheeky sheep peering out from below the manger of the Christ child. There were English early medieval superstitions attached to the twelve days of Christmas. For example wind on the eleventh of the twelve days meant that all cattle will perish. If the mass-day of mid-winter fell on a Sunday ‘sheep shall thrive’; if on a Tuesday , they were imperilled, but if the mass-day of mid-winter fell on a Saturday ‘sheep will perish.’

I write about the dramatic events of King Edward’s mid-winter feast at Westminster in 1065 in my novel The Handfasted Wife, the story of Edith Swanneck, to be published by Accent Press in 2013.