I have long been fascinated by medieval wall paintings whether they are in tiny churches in Greece where I have spent much of the last year or in closer to home English medieval churches.

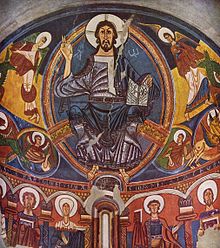

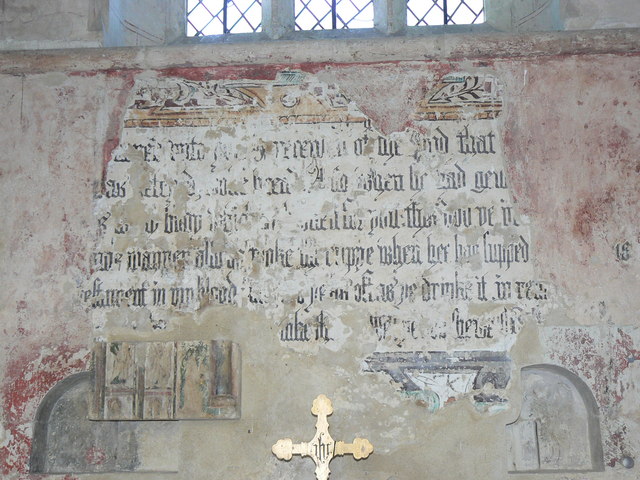

Wall paintings are very beautiful and, like tapestries from the same period, are a picture book of stories used to decorate and to instruct in a world where literacy was restricted to priests and the wealthiest nobility. Features of Anglo-Saxon wall painting did not disappear with the Norman Conquest but along with other aspects of Anglo-Saxon culture merged with new art forms brought to England from the continent, particularly Romanesque architecture.

Little evidence survives of eleventh century painted plaster. Most wall paintings would have belonged to churches although I like to think that palace walls and those belonging to great halls may also have been decorated. These buildings were constructed of wood and so in domestic buildings evidence has vanished. I introduce wall paintings into The Handfasted Wife on the exterior walls of Reredfelle, a hunting lodge on the borders of Sussex and Kent which once belonged to Earl Godwin and in the Reredfelle chapel where what is known as a Doom painting becomes integrated into the story’s narrative. Wall paintings also appear in a secular way in my work in progress, The Countess of the North, a story about King Harold’s daughter and her elopement with a Breton knight.

Fragments of Anglo-Saxon wall paintings have been excavated so we have an idea of what they were like. For example, painted stone work was discovered in Winchester in 1966. It had been reused in the foundations of the New Minster circa AD 901 but it is much older. It shows the remains of three figures and a border of what is known as pelta-pattern which is similar to sub-antique ornament shown on Carolingian manuscripts. The figure style is similar to the manuscript illumination used in the second quarter of the tenth century in Winchester. The cultural links with Carolingian art is apparent in English art of the period and in Norman writings such as The Song of Hastings ( 1068), a praise poem written to celebrate William’s victory over King Harold at Hastings.

Fragments of Anglo-Saxon wall paintings have been excavated so we have an idea of what they were like. For example, painted stone work was discovered in Winchester in 1966. It had been reused in the foundations of the New Minster circa AD 901 but it is much older. It shows the remains of three figures and a border of what is known as pelta-pattern which is similar to sub-antique ornament shown on Carolingian manuscripts. The figure style is similar to the manuscript illumination used in the second quarter of the tenth century in Winchester. The cultural links with Carolingian art is apparent in English art of the period and in Norman writings such as The Song of Hastings ( 1068), a praise poem written to celebrate William’s victory over King Harold at Hastings.

Anglo-Saxon painted plaster has in recent decades been recovered from other sites such as Monk Wearmouth near Jarrow where late 7thC to early 8thC fragments belonged to monastic buildings. A timber and wattle building in Colchester may have been a royal chapel. There, fragments remain of the wall paintings including an eye and draperies belonging to figures that may have been life-sized. Other wall painting images include the remains of four angels around the top of the chancel arch on the Nave east wall at Nether Wallop ( shown above) near Winchester. The angels were presumably shown supporting a figure of Christ in Majesty. The Carolingian linear style is very like that on late 10th C Winchester manuscripts. Hem lines are fluttering and the angels wear bulky flying folds that fall over their bodies.

Wall paintings were executed at the royal nunnery of Wilton as a result of new building works directed by Queen Edith, Harold’s sister, just before 1066. Goscelin, one of Queen Edith’s scribes, left an account of her major scheme of works. Saint Edith’s timber chapel was added to the main church there. It was decorated with paintings of Christ’s passion. Major schemes survive after the Conquest in Sussex churches such as Clayton and Hardham dating from 1100. Here we have the cultures mingling. The iconography and style derive from Anglo-Saxon painting yet the overall effect is Romanesque in Norman tradition. On the Bayeux Tapestry depiction below to the right is thought to be an abbess, possibly another of Harold’s sisters, though unconfirmed, standing in the archway of what may be Saint Edith’s Chapel at Wilton where Queen Edith undertook building works and wall paintings during the mid eleventh century.

1066 did not make a clear break with Anglo-Saxon traditions of plaster painting. As the terrible effects of Conquest gripped the land aspects of two different cultures mingled, and this is the sense that I try to integrate into the background ‘wallpaper’ of both novels, The Handfasted Wife and my ‘work in progress’, Countess of the North, a story about King Harold’s daughter Gunnhild.

The Handfasted Wife, a story of Edith Swan-Neck, is published by Accent Press and is available from Amazon UK and USA as a paperback and for kindle. It is available from Accent Press on line bookshop and for all e readers.