Elizabeth Cromwell and Female Cloth Merchants during the Early Tudor Era

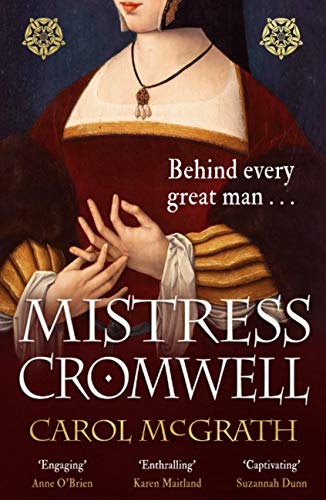

To celebrate the republication on Thursday 25th June of Mistress Cromwell, originally published as The Woman in the Shadows, I have written this article to explain the novel’s background.

Mistress Cromwell is set in London during the first three decades of the Tudor Era. Some historians, including myself, would consider this to be a transition period between the English Medieval period and the Early Modern Period. It’s a time that heralds in the English Renaissance. It also was a period of Humanist thinking. Modern men of the time, such Thomas Cromwell and Sir Thomas More, were passionate about interrogating ancient documents, particularly those written in Latin and Greek. They were increasingly aware of their individuality as men. The first half of the sixteenth century was also a successful time for the English cloth trade. Merchants dominated London’s guilds. Much money was to be made by the merchant class and many were powerful and very wealthy. This was a time of opportunity for those with ambition and talent. Thomas Cromwell, one such talented Tudor, famously rose in London circles, as a cloth middleman and a lawyer whose talent was for conveyancing as well as trade disputes. He, of course, entered Cardinal Wolsey’s service probably first of all in a law man capacity. As Wolsey fell from power Thomas Cromwell was drawn into the King’s orbit where eventually he rose to become King Henry VIII’s chief minister. Mistress Cromwell is his wife’s story.

Thomas Cromwell

Elizabeth Cromwell, wife to Thomas Cromwell lived during the first three decades of the sixteenth century. Elizabeth is the protagonist and heroine of Mistress Cromwell. This novel is her story, researched from whatever scant sources are available about her life. Not much was ever written about Elizabeth. She was the daughter of a Putney Cloth Merchant, Henry Wykes. Since trade often married into similar trades, it is likely that her first marriage to Tom Williams, a man belonging to the King’s Yeomen, was also into a cloth merchant’s family. Her second marriage to Thomas Cromwell was similar and yet different. Thomas Cromwell was a cloth middleman. Moreover, he was a self-taught lawyer and at this time he took on legal work for The Merchant Adventurers. Elizabeth and Thomas married in 1514, long before Thomas Cromwell became involved in the King’s Great Matter, the dissolution of King Henry’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon and the dissolution of England’s monasteries, abbeys and nunneries.

Tudor London

I suggest that Elizabeth, by 1513/14, was a widowed female cloth merchant and, in this novel, I compensate for the lack of specific knowledge about her life by researching Thomas Cromwell himself, and the London Merchant Class, aiming to write a portrait of a woman who was firstly a widow, a merchant in her own right and wife to an ambitious man.

What do we know about female traders during this era?

It is well-known that for women, and for men also, marriage throughout the medieval period and into Tudor times could enhance their working lives. Business in this period was often based on a partnership. A town wife’s co-operation in her husband’s business was as important to the success of that business as that of a peasant wife working in the fields was to the labouring family’s survival. The Ordinance of Founders in 1390 stipulated that each master could have only one apprentice unless he had no wife. In this event, that of bachelorhood, he could have two apprentices. A wife’s contribution to the family business was significant. Since Elizabeth probably had an education she could, for example, have kept account books for her husband’s family business. Several centuries had passed since the Ordinance of Founders. By Tudor times, more apprentices were permitted. Interestingly, girls were often apprenticed to trades in the same way as boys. Wills written by craftsmen often leave provision for their daughters as well as their sons to be apprenticed. Girls were apprenticed to men as well as to women. Even so, it was more usual for female apprentices to be under the tuition of the master’s wife and live in the mistress’s house as part of the family.

Wives and daughters were engaged in the craft work of the household, whatever this work was. A woman could be an armourer, a female merchant like Elizabeth, a book-binder, a fletcher. Women were even found loading wool onto ships. Guild regulations which prohibited women from fully entering many trades did allow for the wife’s contribution. It was a wife’s expertise that allowed her to continue her husband’s trade should she be widowed. Women could follow a path of her own. For example, if she lived in London or other large trading towns such as Bath, Bristol, Lincoln, a single or married woman might become a femme sole. She would have full responsibility for managing her own business. As a femme sole a woman could face legal charges concerning her business. She could be fined and even go to prison for male-practice or debt, whilst her husband remained untouched by law. He would simply not be accountable if his wife registered as a sole trader. On the other hand, if a business was shared, the property would by law belong to the woman’s husband who is then responsible for any legal charges incurred.

The widow who did not remarry fulfilled many masculine roles. She could take her husband’s name as her own or she could revert to her maiden surname. In Mistress Cromwell, Elizabeth continues to trade as Elizabeth Williams, using her deceased husband’s name. A new marriage might endanger her legacy so, within the novel’s context, Elizabeth is reluctant to throw away her freedom when she is pressed by her father to remarry. That is, until she meets Thomas Cromwell and makes a marriage of her own choosing.

In London city law and common law combined to give the widow an attractive package. Legitim which applied to widowhood was a law of thirds, a third to the widow, a third to the children and a third part for the Church. However, in the City of London, by common law rules, legatim could be ignored. Elizabeth had no children by her first husband and therefore she inherits his entire business. A London merchant widow could invest goods and property as she wished.

The picture above shows Austin Friars garden. Its a replica of Thomas Cromwell’s garden. He loved gardening and Mistress Cromwell opens in this garden. Of course there were no buildings then such as you see in the photograph. It was larger too.

A potentially wealthy widow like Elizabeth would be wooed relentlessly. Business as usual was expected, so Elizabeth carries on her husband’s cloth business after his demise. Widows were entitled to take up the freedom of the City. This bonus gave a woman the right to carry on her trade, freedom from tolls throughout England (great if you were exporting cloth through a port other than London) and permission to maintain her husband’s apprentices as well as take on others. Widows were regarded as ‘goodwives’ in Medieval and Tudor England. The term is frequently used in the novel.

Male jealousy often surfaced over competition from female labour. Life could be tough for a female trader. Barring women from trades (by the guilds) did happen. Women’s wages were lower than a man’s for the same work, thus men were afraid of being undercut by cheap labour. There were women members of craft guilds, but, importantly, these women were usually widows, not femmes soles. Moreover, women were rarely admitted as full guild members.

We find women employed in all stages of cloth production from combing and carding wool, spinning of yarn and weaving, though men often were found to be occupied as weavers. Female cloth merchants were, like Elizabeth Cromwell and Chaucer’s Wife of Bath were often discovered amongst the big clothiers of England during the late medieval period. To survive, they had to be tough and ruthless, particularly in Tudor London.

Find Mistress Cromwell on amazon or order from your bookshop. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing this novel. Amazon link below.

https://smarturl.it/MistressCromwell

If you are interested in further reading I suggest:

Eileen Power Medieval Women published by Cambridge University Press

Tudor Women by Allison Plowden published by Sutton Publishing

Medieval Women by Henrietta Leyser published by Phoenix Press

Follow me on amazon @Carol McGrath

and on my website www.carolcmcgrath.co.uk