Exactly one year ago I took to the pilgrim route from Ferrol to Santiago de Compostella. It was the one favoured by the English pilgrims who sailed to either Ferrol or A Coruna to begin their pilgrimage to the shrine of St James. This experience reminded me of how much travel went on throughout the Middle Ages. Pilgrim routes were of extreme importance in our past, a chance to get away from it all, visit foreign lands and, since God was the ever present and dominant aspect of medieval Christian existence, the medieval traveller might seek miraculous cures from illnesses or simply become absorbed by prayer and contemplation.

Pilgrimage has been immortalised in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales where there appears a gallery of not so devout pilgrims. In Chaucer’s work, characters from a variety of walks of medieval life are represented on pilgrimage to the tomb of Thomas a Becket in Canterbury and, famously, they tell stories as they travel. The Canterbury Tales is worth reading and re-reading over and over if only to find in it brilliant snap shots of fourteenth century existence, stories and journeying. It is not the only text that embraces medieval travel. For instance, Anglo-Saxon poetry is filled with wanderings and The Bayeux Tapestry depicts ships, horses, goods and waggons.

Travel in the Middle Ages was equally associated with trade. The occupant of the early seventh century ship burial at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk was buried with an array of artifacts that give an overt message of the wealth the controlling groups within Anglo-Saxon Society possessed. Settlements were reasonably self sufficient but industrial centres for mass produced pottery existed by the ninth century as for example at Ipswich in East Anglia. At this time the potter’s wheel was introduced into England. Lead based glazes which produced orange, brown or yellow colours were produced at Stamford, Lincolnshire and at Winchester, Hampshire.

Stamford ware has been found in Ireland and Scandinavia. Pottery travelled, as did metalwork and exquisite early English tapestry work, beautiful embroideries, and wool, too, became English exports throughout the Middle Ages. Then there is glass. In early Anglo-Saxon England the main source for glass was Ravenna in Italy. Cubes known as tessararae were traded throughout Europe for reworking into vessels or beads. But larger imported objects such as lava quernstones from Niedermendig in Germany found their way, too, into early Anglo-Saxon graves. Elephant ivory, whose origins lay in East Africa or India was, in fact, a surprisingly common artifact in early Anglo-Saxon England. It was particularly used in bags and pouches, and has, according to Sally Crawford, writing in Daily Life in Anglo-Saxon England, frequently been discovered as an incinerated artifact in cremation urns.

The Viking influence, she writes, on Anglo-Saxon England cannot be underestimated. The Danish Vikings were traders as well as raiders and their settlement in England was rapidly followed by urbanisation. Excavations at York and in East Anglia have revealed the extent of manufacturing and production that took place from circa 866. Glass making furnaces were introduced and other crafts were established in York to include woodworking, stone sculpture, leatherworking and boneworking. Equally, the wealthier inhabitants of Viking Age York could buy Rhenish wine and lava quernstones, sharpening stones of Norwegian schist, amber and soapstone from Scandinavia and silk from Byzantium. Bald’s Leechbook contains a number of remedies requiring exotic spices, including cumin, pepper and coriander and it is possible that the exotic ingredients included in Bald’s recipes could be found in the markets of York and London. The merchant in Aelfric’s Colloquy explains how he made his money by filling his ship with English goods which he sold on the Continent, then returned to England with continental luxuries such as precious metals and clothing, purple cloth and silks, elephant ivory and tin, sulphur and glass which he sold in English markets.

Most journeys in early medieval England were local and carried on foot and as most of the population was tied to the land access to travel was limited. In Kent a series of old droveways have been identified that connected manor estates to the forests of the Weald. Roads acted as boundary markers as well as being a corridor for movement. Roads were also places where kings showed and the major highways represented an aspect of the king’s power. To travel on the road was to recognise the right of the king to control his people’s travel. To travel off the road was prohibited and restricted by law. Harold’s journey of 442 kilometres from Yorkshire to the South coast after the Battle of Stamford Bridge was impressive. It was accomplished in a fortnight. However, this journey was not unique to the Anglo-Saxon world. King Athelstan and his court only took eight days to travel from Winchester to Nottingham a distance of 248 kilometres.

The Anglo-Saxon elite travelled overseas generally to Rome on pilgrimage. Churchmen travelled in large groups. Women were warned to be careful of their moral welfare in Italy. Pilgrim routes also existed across England to Glastonbury. People went to see saintly relics. The horses of the Anglo-Saxon elite often had decorated harnesses with spangles of tin or silver. Silver decorated stirrups have been found by the river Cherwell in Oxfordshire. Carts and waggons were used to carry people and goods and sometimes these were pulled by hand rather than by animals! Rivers were important routeways. The monks of Abingdon Abbey cut a large canal across one of their meadows to ease traffic of goods. Ships and seafaring are important in Anglo-Saxon life. Poems and other texts also give a picture of the hardships suffered by early medieval sailors. The Gaveney ship built around AD 900 was carrying a cargo of hops and may have been bound for Canterbury, Rochester or London when it sank.

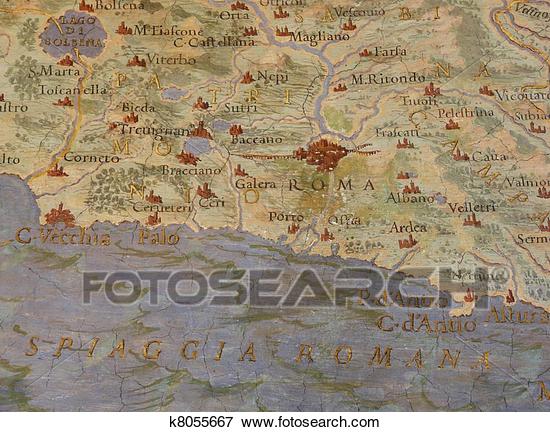

As for early maps, they mostly existed in the form of lists compiled by those who had travelled the route already and these lists referred to places based on the first-person experiences of others. As early as the fourth century there are reports of pilgrimages with an itinerary originating in Bordeaux that suggests the best route to follow to the Christian sites in Jerusalem. In the seventh century the bishop Adoman wrote a book on the holy places, based on the experiences of another bishop a few years earlier. It was illustrated with ‘measured drawings’ of the churches of the Ascension and Holy Sepulchre. Travellers generally did not make use of maps in the Middle Ages. They sought the advice of local guides or joined groups, such as the pilgrims in the Canterbury Tales. Later Medieval maps were used by scholars, such as those wishing to interpret the Bible. Charts were used by administrators at home and were rarely taken to sea. However, features of medieval maps such as the inaccessible garden of Paradise and the peculiar hydrology of the four rivers flowing from it were difficult to hold to against the first-hand experiences of travellers. By the end of the fifteenth century the actual experience of sailing around the sphere that is the world became a transforming and perhaps disturbing discovery as old belief systems became challenged and new lands were discovered that were full of previously unknown nations.

Finally, back to Compostella. The twelfth century Pilgrim’s guide to the route to Compostella describes the four common routes and the sights and dangers encountered along the way. This is an early medieval list and here is a medieval warning from the guide:

On leaving that country of Gascony, to be sure on the road of St James, there are two rivers that flow near the village of Saint-Jean-Sorde, one to the right and one to the left, and of which one is called brook and the other river. There is no way of crossing without a raft. May their ferryman be damned! Though each of the streams is quite narrow they have the habit of demanding one coin from each man, whether poor or rich, whom they ferry over, and for a horse they ignominiously exort by force four.