Today I welcome medieval Historian, Paula Lofting to The Writers’ Hub. Paula has just published, with publisher Pen & Sword, probably the best non-fiction book about Harold Godwinson, his times, rise to power and importantly The Norman Conquest that I have read… and I have read many books on this subject. The narrative in Lofting’s scholarly book is delightfully readable with an, at times, conversational style. This book is very well supported with references, primary and secondary, and has an interesting photo section.

The author’s analysis is present throughout and it’s spot on. I don’t think I have ever come across such a comprehensive study of the Godwin family, the background to Harold’s kingship in 1066, his life, disputes, and his successes as thoroughly researched. I particularly enjoyed reading about Harold’s establishing the Canons of Waltham Abbey, about his stroke when a young earl and his links with East Anglia including his hand fasted marriage to the love of his life, known to History as Edith Swan-neck.

Edith Swan-Neck is always of interest. It is a romantic story. She was a wealthy East Anglian heiress and mother of Harold’s sons and daughters, all six of them living in 1066. Harold married twice, the second time with Church blessing in 1066 and for political reasons. Harold Godwinson, in fact, had two wives.

It’s a fabulous book and the author has generously provided The Writers’ Hub with a wonderful article about questions around King Harold’s death. It really is a mysterious story in that there have been several locations suggested for his burial. What follows is an article and a little info about the writer herself. Paula Wilcox’s knowledge on her subject is second to none.

The Death of Harold and Last Resting Place by Paula Wilcox, author of Harold, the Last Anglo-Saxon King

‘He was the ‘darling of the clergy, the strength of his soldiers, the shield of the defenceless’ Waltham Chronicle, written during the twelfth century.

In today’s penultimate blog hop post, I thought it would be fitting to discuss both Harold’s death and the search for his last resting place, using excerpts from Searching for the Last Anglo-Saxon.

Firstly, I want to thank everyone who hosted me, including Carol, Anna Belfrage, Lisl Madeleine, Annie Whitehead, Lynn Bryant, Samantha Wilcoxson, Cathie Dunn, Joanne Major, Eleanor Swifthook, and Tony Riches. They are amazing authors and people, go read their books!

Thanks also to Samantha Wilcoxson for making and designing the banners!

The Death of King Harold II and his Last Resting Place by Paula Wilcox

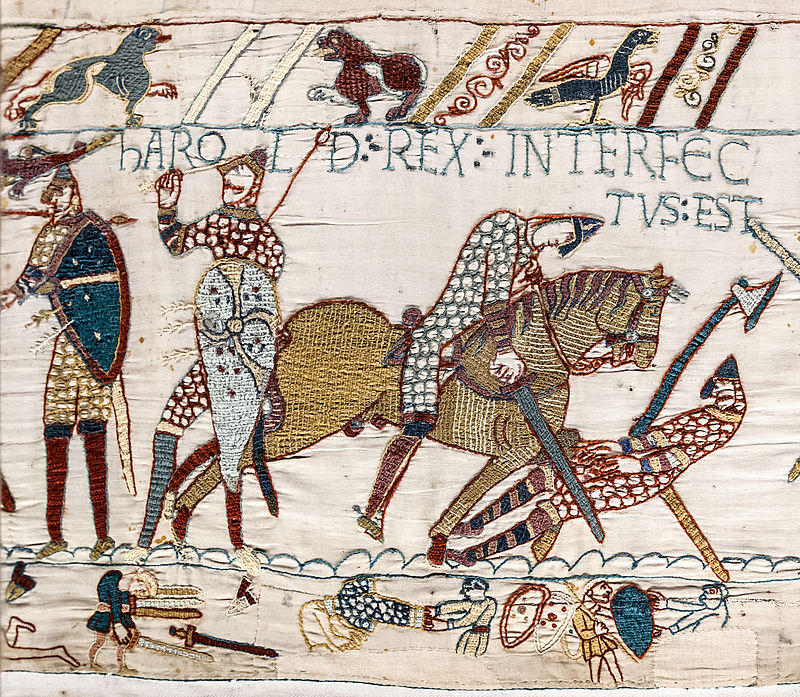

Much has been made about the death of King Harold II over the years, that he was wounded by an arrow in the eye at the Battle of Hastings that took place on 14 October 1066. This was said to have brought about his slaughter. Once down and injured, chaos was wrought amongst Harold’s men and the invading Duke William, therefore allowing his hit squad to break through the huscarls’ defence and cut him down. Many of the sources are confused, but the earliest source we have for Harold’s death, Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, The Song of the Battle of Hastings, mentions no arrow in the eye, just that he was viciously cut down by William and his men. The Bayeux Tapestry is a fabulous visual source for the events of 1066, especially as it is contemporary, however the scene where the man ‘Harold’ is pulling on the arrow that appears to have been shot into his eye, has been thought to have been tampered with during repairs the 19th century and that the original panel shows that he had a javelin shaft in his hand that he was about to throw. There is also an image which shows a man being cut down by a mounted warrior who wounds his leg, mentioned by 12th century writer, Malmesbury. The Carmen explicitly states which of William’s men does what to him. Its quite graphic and not very pleasant.

An Excerpt from Searching for the Last Anglo-Saxon King:

The duke gathered his best knights together, Eustace, Hugh, and a knight called Gilfard. They charge to Harold’s position, cutting a swathe across the field spurring up to the ridge. There was the king, the object of William’s ire, surrounded by his huscarls valiantly protecting him. Anyone in the way of the French soldiers’ was slaughtered until they reached their prey.

Guy of Amiens, writing shortly after the events, solemnly tells us:

‘The first of the four pierced his (Harold) shield and chest with his lance, drenching the ground with his gushing stream of blood; the second cut off his head with his sword, below the protection of his helm; the third pierced the innards of his belly with his lance; and the fourth cut off his thigh and carried it some distance away. The earth held the body that they had in this way destroyed.’

During the tour we have also discussed how the Papal Banner was never mentioned in the early sources either, as was the arrow not mentioned, suggesting that this could well be the case.

You can read more about the battle and Harold’s death in Searching for the Last Anglo-Saxon King.

Harold’s Last Resting Place – Second Excerpt from the book

‘Whatever the truth of how Harold eventually made it to Waltham, there is no doubt that his last journey was the one to Waltham. And there can also be no doubt that he was meant to have been laid to rest in the church he commissioned, the church of the Holy Cross. According to William Winters, the last Anglo-Saxon king was said to have been interred roughly about 120 feet from the present east end of the church. This part of the churchyard is now where the choir of Harold’s church stood, and was once used as a garden by the earl of Carlisle, and the builder of Abbey House, Sir Edward Denny. Today there is a stone slab commemorating Harold, ‘This stone marks the position of the high altar behind which King Harold is said to have been buried 1066’, and another block which says, ‘Harold King of England. Obit 1066’. The author of Waltham Chronicle suggests that Harold was entombed near the high altar, signifying his status as king. He was said to have been translated three times, but it is not known whether his coffin is under the site of the stone slab outside the modern-day church or whether he was moved elsewhere. ( The author’s son’s photograph taken inside the Abbey Church).

My lovely guide, Tricia Gurnett of the King Harold Society, to whom I am grateful for spending time with, showed me around Waltham Abbey that chilly day in March, advised me that the King Harold memorial standing stone was scanned six years ago, about the time the stone underwent a restoration. It was examined using a radar to see if anything had been inside it when it was erected in the 1960s. It was found to be empty. Ms Gurnett also explained on good authority that no coffin or remains thought to be Harold’s, have ever been found. As we know, Harold’s body had been moved at least three times during the building work when his church gave way to the Norman building and then to the great Waltham Abbey of Henry II, but the remains of the king have since disappeared. With the amount of internments and the removal of remains to fit in new burials in over 900 years, it would be surprising if anything of him still remained. Another scan of the churchyard was made in 2014, involving a theory by author Peter Burke and Oval films, but nothing ever seems to have emerged, not even the proposed documentary. Whether or not he was moved from there at some later point to a different location we cannot know. Despite this he could still be there somewhere and whether or not he is, it does seem that this was his intended place of rest.

That Bosham is a candidate for Harold’s burial is hardly surprising, it was after all his childhood home and probable place of birth. It is quite likely, one historian claims, that his mother would have wished for his body to have been buried in the home that she loved and suggests that Hastings was close to Bosham, therefore easier to get to than Waltham, but the actual distance is not much different between the two. Gytha would have known what her son’s wishes were. As his mother, it is unlikely that she would have gone against the vision he had for himself. That he adored Waltham is evidenced by the care he took for it, his establishment of the collegiate, and his adornment of the church with many beautiful items and holy relics. With the battle over and England’s fall evident, Gytha’s time at Bosham was running short. Having been her son’s property, it was now William’s. The Holy Trinity Church next door to it was in the hands of Osbern as it had been before the conquest, but he was Norman and related to William. With all this in mind, Bosham seems doubtful.

There might have been a case for Bishops Stortford; some of the evidence produced by McKenzie and Muff is reasonable, such as the fact that Eadgifu and Harold both held land there, but this does not mean that their connections to the place were as strong as they were in the case of Waltham, which was mentioned by a variety of sources to have been the place that Harold’s body was transferred. Harold’s establishment of the church in Waltham offsets any idea of him being buried in St. Michael’s unless he was moved there later, which is not impossible, but evidence is lacking. The claim that the cousins make about Bishop’s Stortford being Eadgifu’s home seems unusual, for it would be more likely that the couple spent much of their time closer to Waltham, especially whilst it was under construction. If anything, local tradition has it that they lived at her home in Nazeing. (Below see the author as Gytha and another rein actor as Edith Swanneck on the battlefield discovering Harold’s body parts).

Eadgifu’s association with the canons of The Holy Cross and her presence on the battlefield in the aftermath of the death of thousands of Englishmen and their king, is not denied by the Stortford legend. It is just whether or not Eadgifu decided to bring him ‘home’ to the manor in Hertfordshire or Waltham. Stortford is hardly connected with Harold, though Waltham is readily associated with him in various texts and was the place where he had prayed for his life twice. It seems natural that he would have wanted to be lain to rest in the church he had built in recognition of God’s intervention in his illness. Throughout the construction of his church, Harold would have been there as much as he could, overseeing, and if Eadgifu’s home was but 5 miles from the place, he could have easily gone between his manor at Waltham and Nazeing. Stortford tradition implies that a man of tall stature was buried within the coffin found there, but this in no way lends itself to Harold who was said to have been dismembered and badly mangled. And it seems unusual that they did not open the other two coffins meant to contain both Harold’s wives. How could they have known who they were if they had not opened them? And if they had opened them at any other time, no record has been found to date. Mr McKenzie and Mr Muff’s case was not taken forward by the diocese, unfortunately, so for now, whose bodies lie in these four coffins cannot be confirmed. It is in hope I will wait for them to be identified one day.

With all this in mind, Freeman’s case is perfectly rational. Harold may well have had two burials. The first was on unconsecrated ground on a cliff on Hastings shore and then perhaps two to three months later, around the time of his coronation, William relented, and allowed Harold’s body to be transferred to Waltham. In doing so, we are able to reconcile Guy and Poitiers with the Waltham story. It is not necessarily what happened, but a reasonable attempt at describing what might have happened. If I had the power to choose I would go for the three-day escorted march from Battle directly to Waltham. It was how a brave king who died fighting for his life and country should have gone to the afterlife.

So what kind of man was Harold Godwinson? As all medieval kings and leaders are, he was a complex individual, capable of good, competent kingship, responding efficiently in times of national crises; but like so many kings before and after him, he made mistakes and everyone will have their own opinion on his failure to secure the kingdom from the Norman invaders. It is hard to look at the distinct scenarios surrounding the events from the vantage point of a thousand years and say what he should have done when we weren’t there. We know nothing of what went down that day, the mental and physical exhaustion, the trauma, and the loss of so many men. Imagine having to fight on when you know your friends, and brothers were dead, and that the fate of your family, your people, rested on your shoulders? Unless one has experienced the life of a soldier in any sort of war one cannot know. We can only envisage what we think we know happened.’

The Last Anglo-Saxon King is very impressive and thoroughly researched, providing a believable analysis of sources available to us. Thank you, Paula, for this intriguing and interesting post and very good luck with Searching for The Last Anglo-Saxon King. Readers can find out more through Paula’s links below.

https://www.instagram.com/paulaloftingwilcox/

https://www.facebook.com/Wulfsuna?locale=en_GB

https://www.threads.net/@paulaloftingwilcox?xmt=AQGzt4dBTQyhpi3KALo3S2LlPFu675xU76a9176zAtMjRdA

https://bsky.app/profile/paulaloftingauthor.bsky.social

Meet Paula Lofting, Paula’s Biography

Paula was born in the ancient Saxon county of Middlesex in 1961. She grew up in Australia hearing stories from her dad of her homeland and its history. As a youngster she read books by Rosemary Sutcliff and Leon Garfield and her love of English history grew. At 16 her family decided to travel back to England and resettle. She was able to visit the places she’d dreamt about as a child, bringing the stories of her childhood to life. It wasn’t until later in life that Paula realised her dream to write and publish her own books. Her debut historical novel Sons of the Wolf was first published in 2012 and then revised and republished in 2016 along with the sequel, The Wolf Banner, in 2017. The third in the series, Wolf’s Bane, will be ready for publishing later this year.

In this midst of all this, Paula has acquired contracts for nonfiction books with the prestigious Pen & Sword publishers. Searching for the Last Anglo-Saxon King, Harold Godwinson, England’s golden Warrior is now available to buy in all good book outlets, and she is now working on the next non-fiction book about King Edmund Ironside. She has also written a short essay about Edmund for Iain Dale’s Kings and Queens, articles for historical magazines. When she is not writing, she is a psychiatric nurse, mother of three grown up kids and grandmother of two and also re-enacts the Anglo-Saxon/Viking period with the awesome Regia Anglorum.

www.threadstothepast.com www://mybook.to/Sonslive

https://mybook.to/Haroldpreorder