What might you discover if you time-travelled to a Tudor brothel?

During the early modern period ordinary English attitudes to sensuality were probably freer than in many other parts of Europe. Foreign visitors to England from the late fifteenth century to the eighteenth century noted how persons of different sexes greeted each other with a kiss on the lips. The scholar Erasmus found it an attractive custom: ‘Wherever you come, you are received with a kiss by all; when you take your leave, you are dismissed with kisses; you return, kisses are repeated. They come to visit you, kisses again; they leave you, you kiss them all around. Should they meet you anywhere, kisses in abundance; wherever you move, there is nothing but kisses.’

The Bathhouse or Stews

Tudor society had double standards. Any sexual positions other than the missionary position with the man on top and woman beneath were rejected as other positions might incite lust. Any approach from behind was condemned because it suggested man was imitating the behaviour of animals. Any position with the woman on top was frowned upon as it inverted sex roles making the woman the dominant partner. Also, the Tudors believed, it reduced the possibility of conception. Use of unnatural orifices such as the mouth or anus and contraceptive notions such as coitus interruptus or the newly invented Venus glove (a crude early condom) was forbidden.

These rules were most likely bent in the stews, the name given to brothels of the time. Sex has always been traded and attitudes to selling sex has always been in flux. Patriarchal and puritanical stances developed in the West by the sixteenth century. For example, in Augsburg after 1508 cockatrices, the euphemism attached to prostitutes, had their noses cut off if they were found soliciting on Holy Days.

It is difficult to research the details of sexual practices within brothels during this period as there is no unbiased testimony of everyday people. We know the opinions of doctors and moralists, but, to my knowledge, we do not have sources representing the voices of sex workers themselves from the early sixteenth century.

To cast back in time, during the thirteenth century sex was at the heart of a good deal of public bathing. In fact, sex and bathing were so closely related that phrases such as ‘lather up’ became sixteenth-century expressions for ejaculation. The medieval word for a brothel was a stew which derives from bathhouses. William Langham’s Garden of Health of 1579 recommends adding rosemary to a bath: ‘Seethe much rosemary and bathe therein to make thee lusty, lively, joyful, liking and youngly.’ Musk harvested from the glands of a civet cat became a luxury item in the stews, along with castor from the anal glands of a beaver and ambergris (which is whale vomit). Lavender was frequently associated with illicit Tudor sex, and prostitutes often smelled of it.

Southwark ( south of the River)

Women in bathhouses used homemade, and often dangerous, dilapidory creams. Whores plucked their eyebrows. An abundance of pubic hair on the other hand was a sign of youth, health and sexual vitality. However, pubic lice could only be eliminated by shaving and this is where the merkin emerges. This was a pubic hair wig which first appeared in 1450, according to the Oxford Companion to the Body. A well-thatched prostitute might be more desirable than a shaved one. Equally, a merkin might be looked upon as signifying disease, concealing the effects of mercury used to treat syphilis. It could, of course, be titillating if tied in place with a silky fine ribbon.

The stews of Southwark were where you might find the most notorious brothels of Tudor London, situated between Maiden Lane and Bankside, close to arenas for bull and bear baiting. They gained their name from the ‘stew ponds’ where the Bishop of Winchester bred his fish (estuwes also was the name of the stove used to heat water for the bathhouses). Southwark was outside the jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor of London and under rent control of the Bishopric of Winchester. During the Reformation the Catholic bishop’s lands passed to the new Anglican Bishop of Winchester. Ironically, the Catholic bishop Stephen Gardiner cemented his relationship with the King by providing him with Winchester geese. This was the name given to Southwark prostitutes, which derives from the bishop’s association with prostitutes.

The stews were closed for a while by King Henry VII in to halt the rising levels of syphilis. The thousands of prostitutes who were evicted from the brothels had no choice but to ply their trade in the streets. A year later, though, they were reopened. On 13 April 1546 his son Henry VIII shut down the Southwark stews again, issuing a royal proclamation forcing the closure of all houses of prostitution in England. This did not end prostitution. In fact, it increased the practice within the City when the ladies moved over the river from Southwark into ale houses or other premises used for purposes other than selling sex.

Flora

Single women working in the stews were forbidden the rites of the Church so long as they continued their sinful life. They were excluded from Christian burial if they were not reconciled before their death. A plot of ground called the Single Woman’s Churchyard was appointed for them. John Stow writing in the Elizabethan era describes the Bishop of Winchester’s house in Southwark as ‘a fair house, well repaired, and hath a large wharf and landing place called The Bishop’s Stairs.’ Interested merchants and nobleman must have landed close by, ferried over the Thames, to visit the stews.

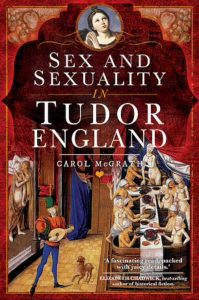

To Buy Link:

Carol McGrath

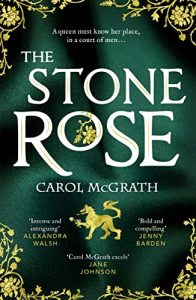

Following a first degree in English and History, Carol McGrath completed an MA in Creative Writing from The Seamus Heaney Centre, Queens University Belfast, followed by an MPhil in English from University of London. The Handfasted Wife, first in a trilogy about the royal women of 1066 was shortlisted for the RoNAS in 2014. The Swan-Daughter and The Betrothed Sister complete this highly acclaimed trilogy. Mistress Cromwell, a best-selling historical novel about Elizabeth Cromwell, wife of Henry VIII’s statesman, Thomas Cromwell, was republished by Headline in 2020. The Silken Rose, first in a Medieval She-Wolf Queens Trilogy, featuring Ailenor of Provence, saw publication in April 2020. This was followed by The Damask Rose. The Stone Rose will be published April 2022. Carol is writing Historical non-fiction as well as fiction. Sex and Sexuality in Tudor England will be published in February 2022. Carol lives in Oxfordshire with her husband. Find Carol on her website:

Follow her on amazon @CarolMcGrath

Subscribe to her newsletter via her website (drop down on the Home Page).

To Buy link: tinyurl.com/3mz4ezx9 My Latest Novel